Sorting

Basic Latin

Unicode based text cannot be sorted by simply comparing code point values, any more than English in ASCII given its separation of upper and lower case.

A typical approach to sorting text will make several passes on the data – commonly three or four. This and following slides introduce the basic concept at a high level for Latin text, as a base for discussion of non-Latin text later.

Prior to the initial collation pass, the data may need to be pre-processed, for example to resolve the underlying order of abbreviations.

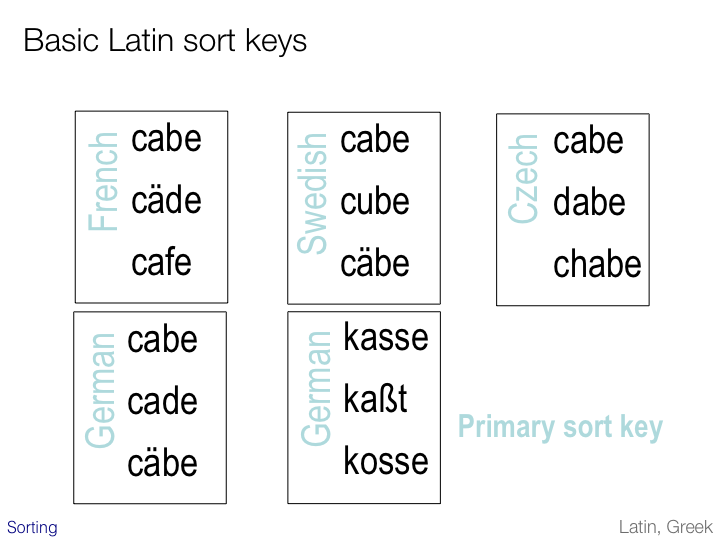

In the initial pass accents are typically ignored in favor of a sort based on the primary letters of the alphabet. In certain cases, however, accents may be an integral part of the primary letters or other criteria may become important. The slide illustrates some examples.

In Swedish, accents create letters that are seen as independent letters of the alphabet. These letters appear after z in the sorted order.

In Czech the sequence of two letters ‘ch’ is treated as a single, primary unit for sorting. Words starting with ch sort after h, not after c.

In German the a-umlaut may be sorted as if it represented two primary letters ae, with no umlaut at all.

Also German provides an example of a primary sort letter than has no equivalent in upper-case. The ß and ss are treated as equivalent for sorting.

Even within a single script these common differences cause the appropriate alphabetic order of letters to vary from language to language.

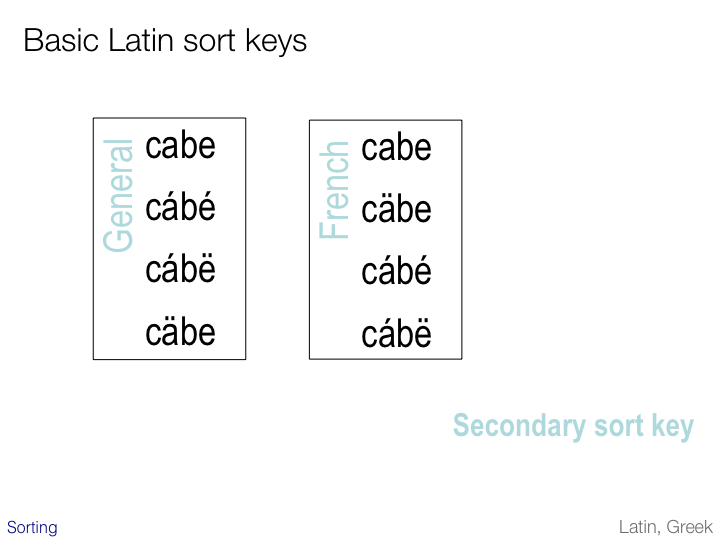

In the second pass accents are typically addressed for entries that would otherwise be the same.

The preferred order of diacritics may vary from language to language, and to some extent from application to application.

The normal way to address ordering is to apply the rules for accent order from the front of the word towards the back. French, however, does the opposite, resulting in the different sequence illustrated on the slide.

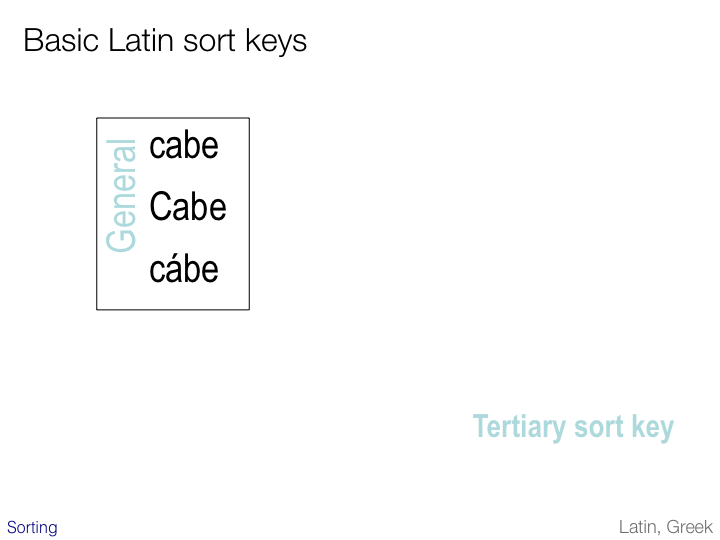

When accents have been dealt with, any differences in case may be addressed in a third pass. Whether upper-cased letters are sorted first or second varies from application to application and platform to platform.

Arabic

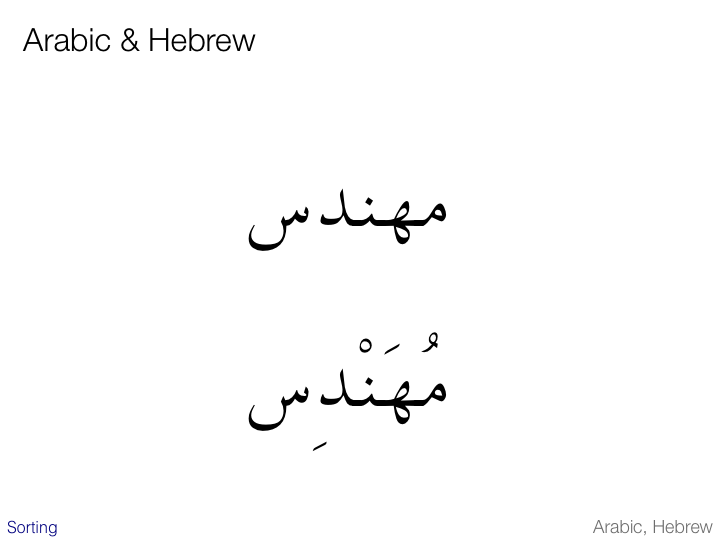

A language written with Arabic script will also need to initially ignore diacritics such as the short vowels so that the two versions of the word above sort in the same place.

Note that, whereas most of the examples on the previous slides typically involve precomposed characters, here we are dealing with one string that has 5 characters and another that has 9 characters.

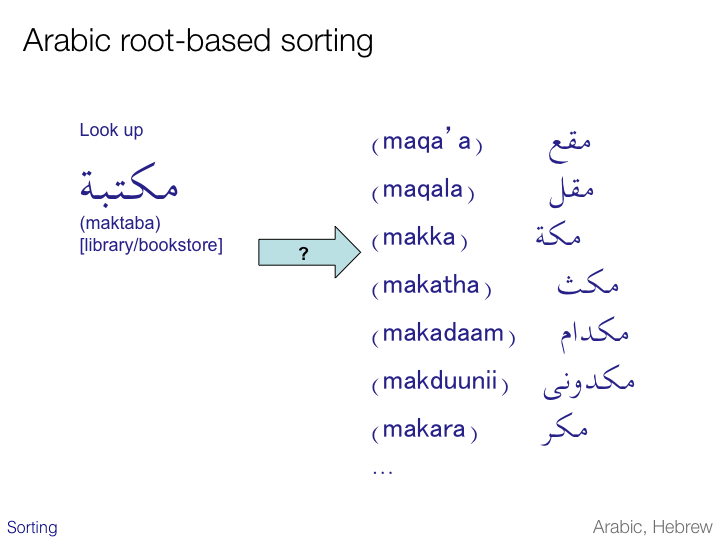

Whereas for most languages using the Arabic script sorting follows the kinds of alphabetic principles already discussed, sorting of words for the Arabic language often uses a much more complicated approach.

If you look for the word pronounced ‘maktaba’ in a dictionary you are not likely to find it in the normal phonetic ordering of entries. This is because Arabic sorting makes use of the fact that Arabic words are commonly based on letter patterns or roots (usually of three letters), and groups words that are based on the same pattern together. In this case the underlying pattern we need to look for is k‑t‑b.

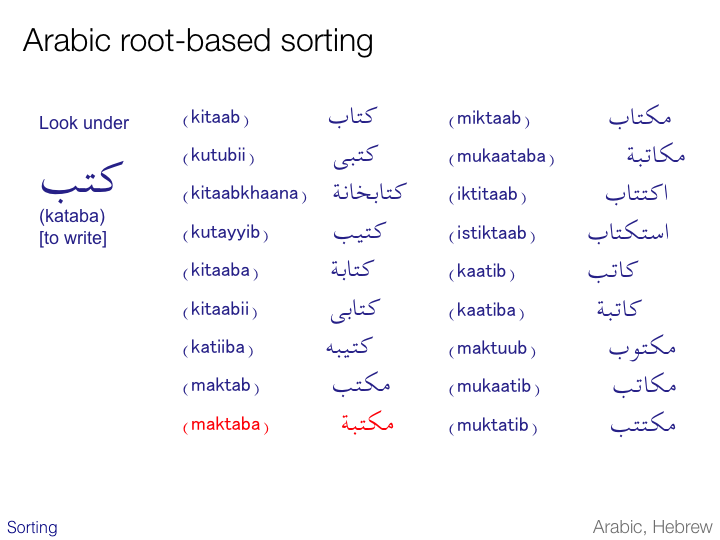

When we look up ‘kataba’ (to write) we will find words such as those shown on this slide as sub-entries, including the word we were looking for, ‘maktab’.

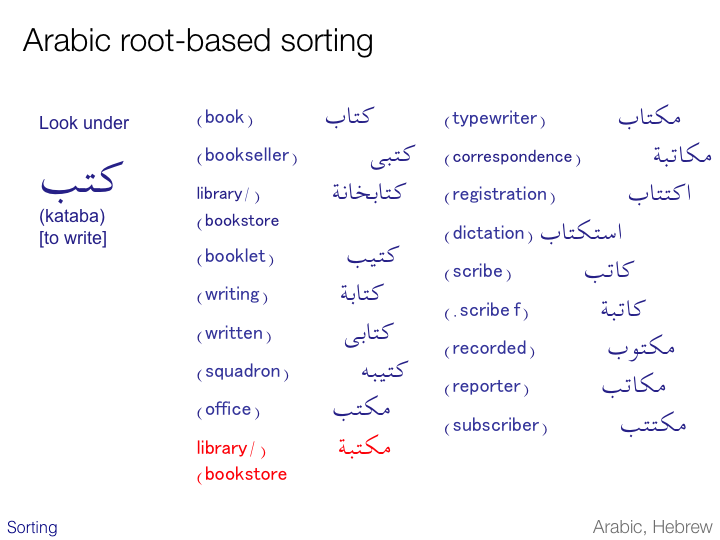

This slide shows the meaning rather than the pronunciation of the words on the previous slide. Note how they are all related in meaning because they share the same root.

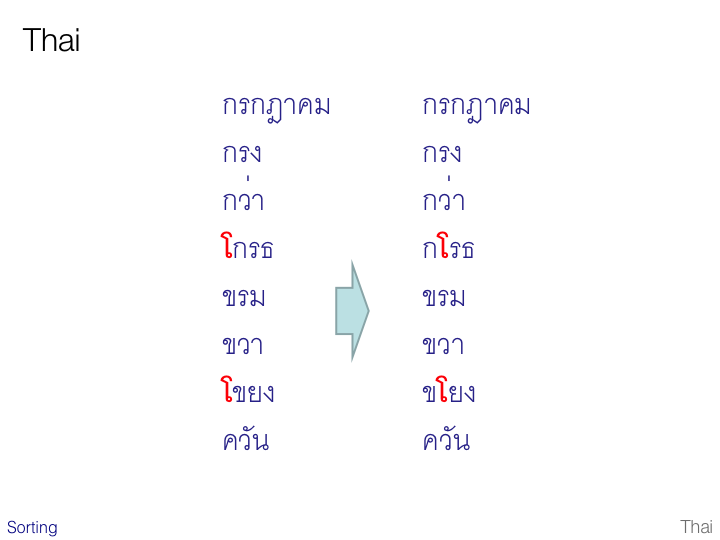

Thai

A sort key for Thai begins with the Thai consonants, then continues with the vowel signs. Thus all consonants without vowel signs come before those with vowel signs. In addition, we have seen how there is often more than one vowel sign associated with a base consonant in Thai. Each of these groups of vowel signs sorts in a unique position.

The slide illustrates an additional phenomenon. Vowel signs that are displayed before the base consonant are sorted as if they appeared after it, ie. following the pronunciation. Because these vowel signs are not combining characters but just ordinary spacing characters in Thai, this means that some pre-processing is typically required before sorting can begin. It also means that words beginning with a vowel sign appearing to the left of its base consonant will appear in many different places in a list of words, as shown above.

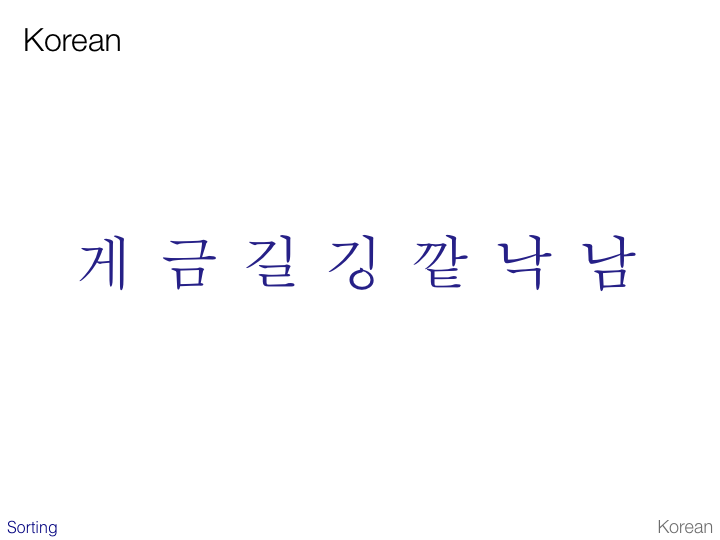

Korean

Korean is very simple to sort in Unicode if you are only dealing with hangul characters, since they are all already in sorted order in the character set.

Of course embedded hanja, Latin text, punctuation and the like introduce additional complexity.

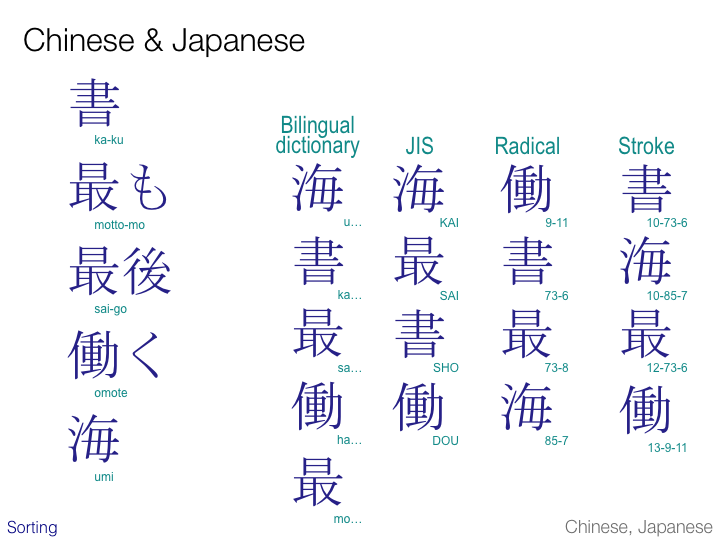

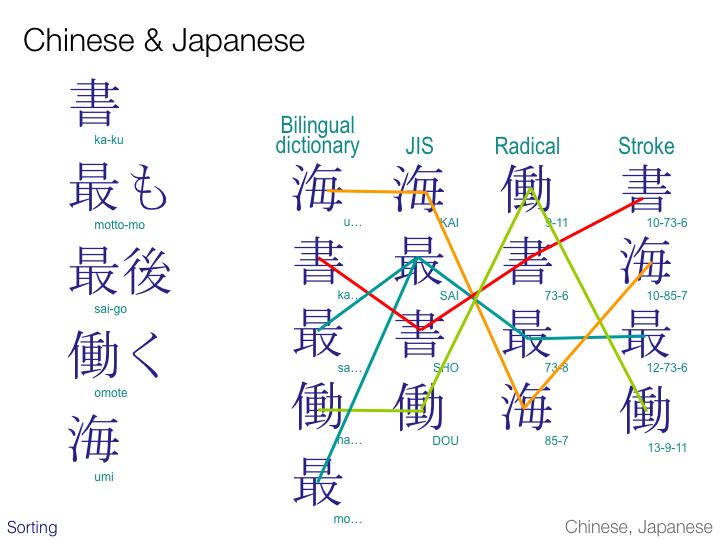

Chinese & Japanese

Chinese and Japanese can be sorted in a number of ways that use a radically different approach. These different sort methods may be application dependent. For example, a bilingual dictionary, an on-line help index, a telephone book, and a kanji lookup table may all sort in different ways.

The slide shows possible orderings for a number of Japanese words.

A typical sort order for a bilingual dictionary would be based on the underlying sound. The order would be based on syllabic sounds, not characters, the same as the traditional ordering of kana syllables (a, i, u, e, o, ka, ki, ku, ke, ko, … ). Because most kanji characters have at least two possible pronunciations, this means that words beginning with a character such as that seen in ‘mottomo’ and ‘saigo’ on the slide sort in different places in the list.

A JIS sort just arranges the characters in order they appear in the JIS coded character set. Common characters in the JIS character set are arranged according to one (usually Chinese-derived) possible pronunciation for that character. You just have to know which sound it is. Less common characters are sorted further down the list by radical (see the next slide). This means that you need to know how common the character is to know where to look for it in the list. All words starting with the same character do, however, sort together.

Radical and stroke ordered lists ignore pronunciation altogether and sort characters on the basis of their shape.

In the former case, the first sort pass uses the radical of each character to sort text according to the traditional position of that radical in the historical list of 214 radicals. (The 214 radicals are grouped by number of strokes, but for radicals with the same number of strokes the order just has to be known. Note that the radical for the character representing the word ‘umi’ is classed as a four-stroke radical, although when the radical appears in the variant form used here the radical is drawn using only three strokes.) Characters that share the same radical are sorted in a second pass on the basis of the total number of remaining strokes in the character. If the radical and the number of remaining strokes is the same for more than one character, you just need to scan the list (entries that start with the same character(s) are grouped together).

Stroke-based sorting starts by ordering according to the total number of strokes in the character. Where there is a tie, the rules of the radical stroke sort are applied.

Multilingual text

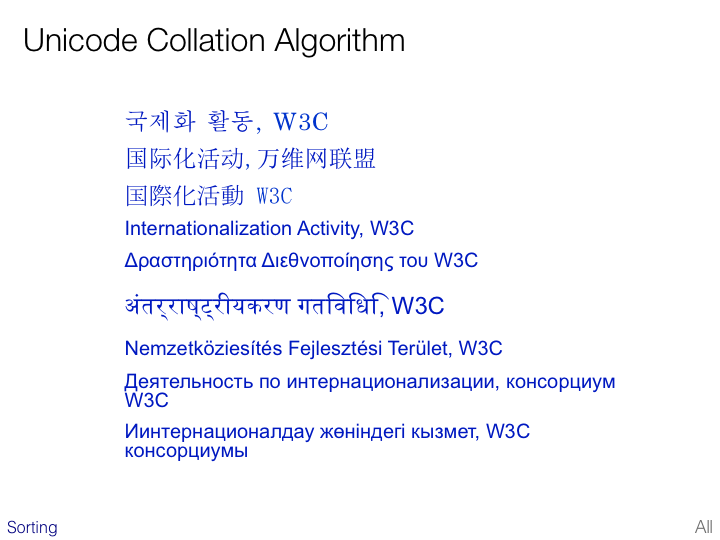

This slide introduces an additional issue when sorting. If you have text in a number of different scripts and/or languages, how do you order them?

The Unicode Consortium has developed the Unicode Collation Algorithm (UCA) to provide a default ordering for multilingual text that is consistent and predictable. This algorithm addresses all the characters in the Unicode repertoire. Note, however, that this is only a default ordering. Language-specific tailoring should be applied to the UCA to help users find text.

Often the most appropriate order may depend on who is reading the list. If a Kazakh is reading the list they may expect to see the Cyrillic entries at the top of the list, not the bottom as shown here. Then one needs to decide how to accommodate any differences between the Kazakh preference for sorting and those for the Russian shown on the slide – both use variants of the Cyrillic alphabet, but you can only sort in the way required by one language at a time.

To achieve true usability, you typically have to know exactly who the user is, and what their expectation would therefore be.

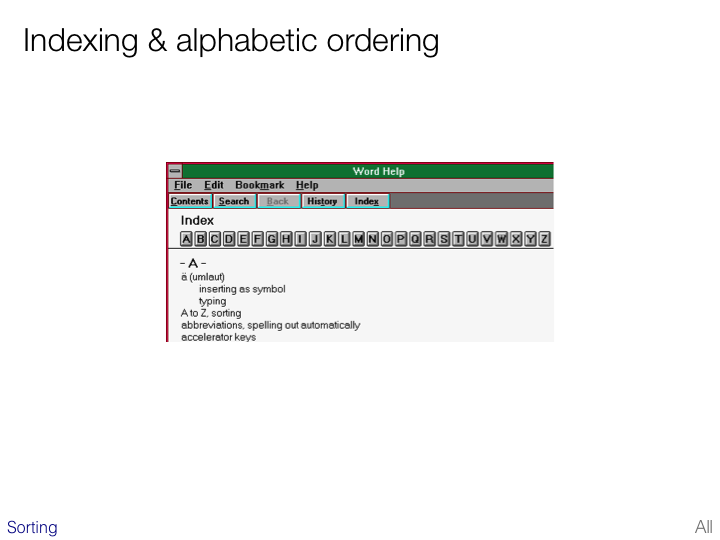

Indexing & alphabetic ordering

The implications of different sort orders mean that a presentation such as that shown on the slide needs significant work during localization. The alphabet at the top and the links need to be changed and the order of all elements in the index needs to be changed.

It is important to ensure that this can be accomplished as easily as possible.

Also, consider the potential cost implications of sorting, say, entries in a reference book alphabetically. The order of the material in the book will need to change during translation.

Content developers should wherever possible use automation to create indices and sorted lists, but those automated tools, of course, need to be able to cope with the necessary range of language- and script-specific tailorings.